🐶 #264 - Who's a good boy?

Forget saving the cat. Show the reader your hero's inner dog.

"In the old days villains had moustaches and kicked the dog. Audiences are smarter today. They don't want their villain to be thrown at them with green limelight on his face. They want an ordinary human being with failings."

–Alfred Hitchcock

Just as audiences have raised our expectations on villains, we're now more demanding when it comes to heroes.

How does a writer convince the audience to trust a character? What marks a character as clearly being a good guy? Here's the hokey example which spawned the titular screenwriting franchise:

I call it the “Save the Cat” scene. They don’t put it into movies anymore. And it’s basic. It’s the scene where we meet the hero and the hero does something — like saving a cat — that defines who he is and makes us, the audience, like him.”

–Blake Snyder

If the scene is too random or disconnected from the specifics of the character and story, it can feel perfunctory —the equivalent of earning a merit badge. Why should the audience consider this specific character to be a hero worth believing in? Let's look at a recent example.

A boy and his (cousin's) dog

In the early parts of Superman (2025), Clark Kent saves many innocent civilians whose lives are put in jeopardy by his fights. There is a funny bit where Superman swoops down to save a squirrel. Not a cat, but close.

None of these moments tell you much about this caped crusader. Saving people in danger isn't specifically a Superman thing. And as many superhero stories have shown us, someone can appear heroic when people are watching, but still be a sociopath.

For us to understand a hero, we need to go beyond showing they're nice or likable. We need to expose the heart of the character.

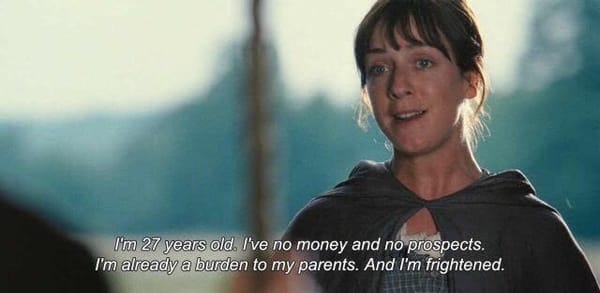

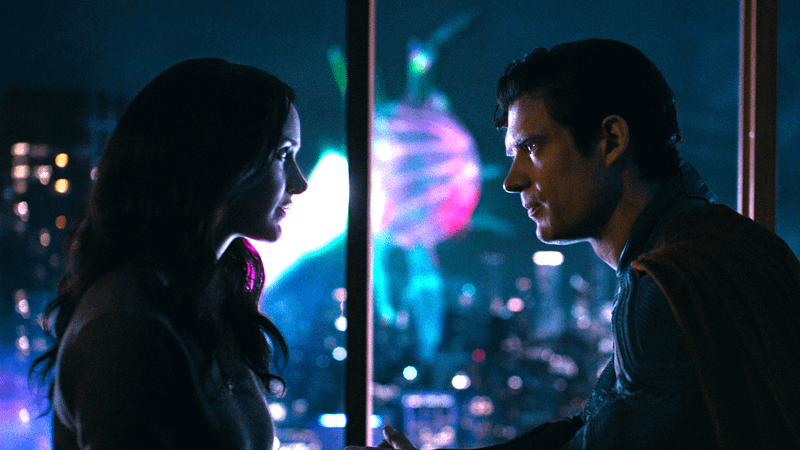

For 2025's Superman, this moment comes when Clark tells Lois Lane he's going to surrender himself to the DOJ in order to get a chance to find Krypto.

Morality check: "Yes, even this one."

I generally agree that there are no bad dogs, just bad pet parents. I'm not here to judge Krypto's behavior.

But Superman does. Kal-El knows this dog is impulsive, stubborn, chaos-in-a-collar. He gets pretty peeved about the damage the dog does to his Fortress of Solitude. Even so, he's not going to shrug it off when Lex Luthor abducts Krypto.

The reason Clark states for trying to save Krypto gives the audience so much more than simply seeing the act.

"If you want to understand any religion or system of beliefs, look for the thing that it most pains them to affirm, but they affirm it nonetheless.

- Prof. Ralph Williams

Showing a character's core goodness requires a test. They make the choice to live by their moral compass at a time when doing so is going to make things more difficult for them.

Dr. Grant hates kids (but not completely)

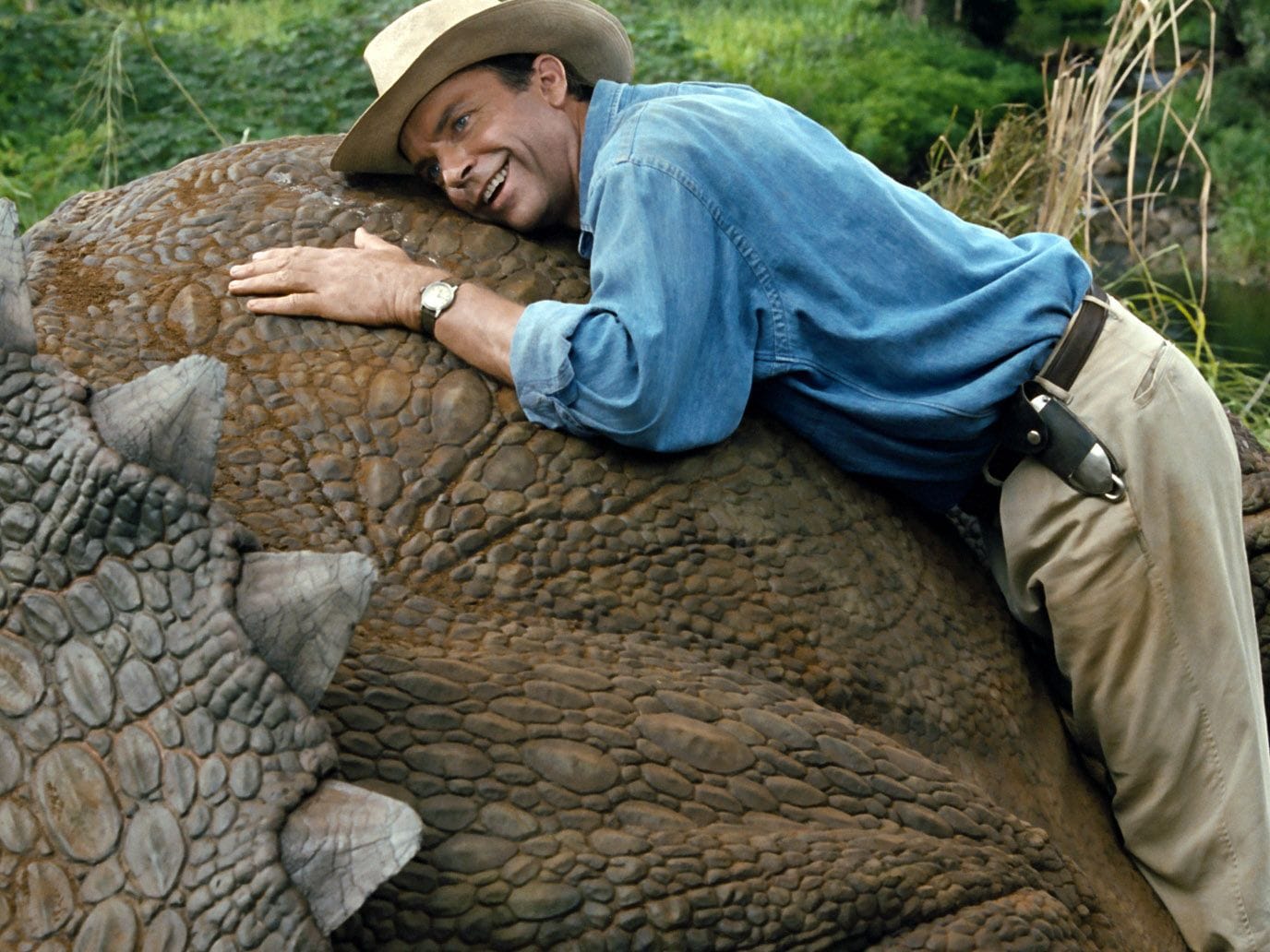

In his first appearance on screen in Jurassic Park, Dr. Alan Grant fights with a computer, waxes poetic on evolution, and scares the crap out of a kid who dared to think that raptors looked goofy. He even uses a fossil of a raptor's toe claw as a prop to drive home the point.

He's smart and cranky from the drop. In scene after scene, Dr. Grant makes it clear he does not like kids and thinks they're annoying, smelly, and in general a nuisance. Dinosaurs > Kids, got it?

So when he's flown to a billionaire's secret cloned dinosaur island, are there kids there? And how. Tim and Lex are the park owner's grandchildren, and Tim is exactly the child-sized Dr. Grant that Dr. Sadler described in her previous defense of parenting. We're reminded of Alan's feelings about kids in the classic Speilberg oner where Tim talks at him about dinosaurs at a mile-a-minute before they get into the jeeps to take a tour of the island.

But all of these feelings of irritation get pushed aside when the T-Rex breaks free and puts Tim and Lex in danger. Dr. Grant jumps into action, and doesn't just get the kids to safety, but starts to empathize with them:

Men will literally climb into a jeep stuck in a tree instead of going to therapy.

Dr. Grant thinks kids are the worst, but he doesn't want them to die. And by protecting them he understands how he can care about kids as much as he cares about dinosaurs. Dr. Grant's moral compass is all about earnestly respecting living things and living in awe of life itself.

Teaching the Arizona Trash Bag

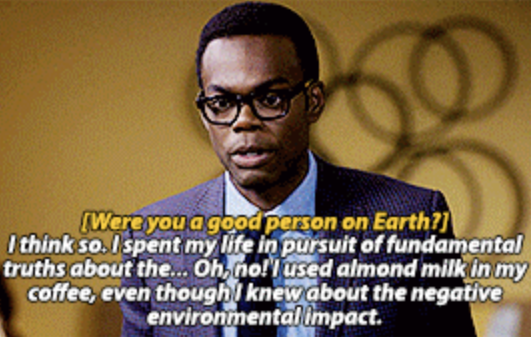

In The Good Place, Chidi Anagonye was a Professor of Moral Philosophy before he died. He literally spent his life obsessing over how to be a good person. So when he's introduced to Eleanor Shellstrop in the afterlife, he's presented with a moral Catch-22.

Eleanor knows she's not a good person ("I was a medium person."), and she doesn't want to be found out and sent to The Bad Place. She wants Chidi to teach her how to be good so she can stay. But if Chidi does this it requires him to lie and deceive everyone else in their neighborhood of The Good Place.

And Chidi already gave himself a stomachache over less directly consequential moral conflicts.

But Chidi chooses to help Eleanor, nonetheless.

His moral compass compels him to try. He believes that people can live a moral life, and that moral behavior can be taught.

Forget the cat. Find the heart.

These are moments where we truly meet these characters. Characters already need to make consequential choices in there story, so which decision do they need to make that puts their morals and worldview in question?

Where can there be a moment that shows us "what it pains them to affirm, but they affirm it nonetheless?"

👋 Are you new here?

Inneresting is a weekly newsletter about writing and things that are interesting to writers. Subscribe now to get more Inneresting things sent to your inbox.

And if you can't wait until next week for more Inneresting, check out the Quote-Unquote Apps Blog where we keep previous issues and other posts about screenwriting and things interesting to screenwriters.

Previously on Inneresting…

In case you missed it, last issue’s most clicked link, featured a breakdown of the climactic confrontation in The Departed put together by From the Screen:

What else is inneresting?

- Craig Mod on walking through Shibuya after years of avoiding it, urban planning, and how “the forces driving mass hyper-consumptive tourism are the same ones fomenting fascism, science skepticism, kleptocracy, billionaire veneration, labubus, and entertaining ourselves with little colored bubbles until the very second before we die.”

- Anthony Waddle made saunas for frogs so they won't die of a fungal infection, and people don't understand why he bothered. "People often ask us to justify why we do our work or explain its broader benefit to society. I often retort with: 'No one asks an accountant, or someone making money from money, what their greater purpose is.' Yet, someone like me working to conserve frogs is treated as if that’s not a real job."

- Talk To Me In Korean explains some of the wordplay and cultural references found in K-Pop Demon Hunters. Come for the explanation of why the demon band calls themselves the Saja Boys, but stay for everything else.

And that’s what’s inneresting this week!

Inneresting is edited by Chris Csont, with contributions from readers like you and the entire Quote-Unquote team.

Are you enjoying this newsletter?

📧 Forward it to a friend and suggest they check it out.

🔗 Share a link to this post on social media.

🗣 Have ideas for future topics (or just want to say hello)? Reach out to Chris via email at inneresting@johnaugust.com, Bluesky @ccsont.bsky.social, or Mastodon @ccsont@mastodon.art