🤬 #273 - Using Words to Hurt People

Generic epithets can be hurtful, but a real cutting insult feels like a scalpel, delicately wielded with an intimate knowledge of what's just under the skin.

Take the recent example where Joyce Carol Oates reads Elon Musk to filth:

So curious that such a wealthy man never posts anything that indicates that he enjoys or is even aware of what virtually everyone appreciates— scenes from nature, pet dog or cat, praise for a movie, music, a book (but doubt that he reads); pride in a friend's or relative's accomplishment; condolences for someone who has died; pleasure in sports, acclaim for a favorite team; references to history. In fact he seems totally uneducated, uncultured. The poorest persons on Twitter may have access to more beauty & meaning in life than the "most wealthy person in the world."

It's the specificity and the detached tone that bring this putdown together. Oates points out the disparity between the average social media user and the owner of Twitter. Without directly saying it, she's pointing to his distinct lack of humanity by forcing the reader to try and picture Musk doing any of these normal, human things.

His responses showed he was rattled. But we're not here for that. Let’s head back into the realm of fiction.

What makes for a strong takedown? When your characters need to unload some emotional damage, how can you make it feel personal?

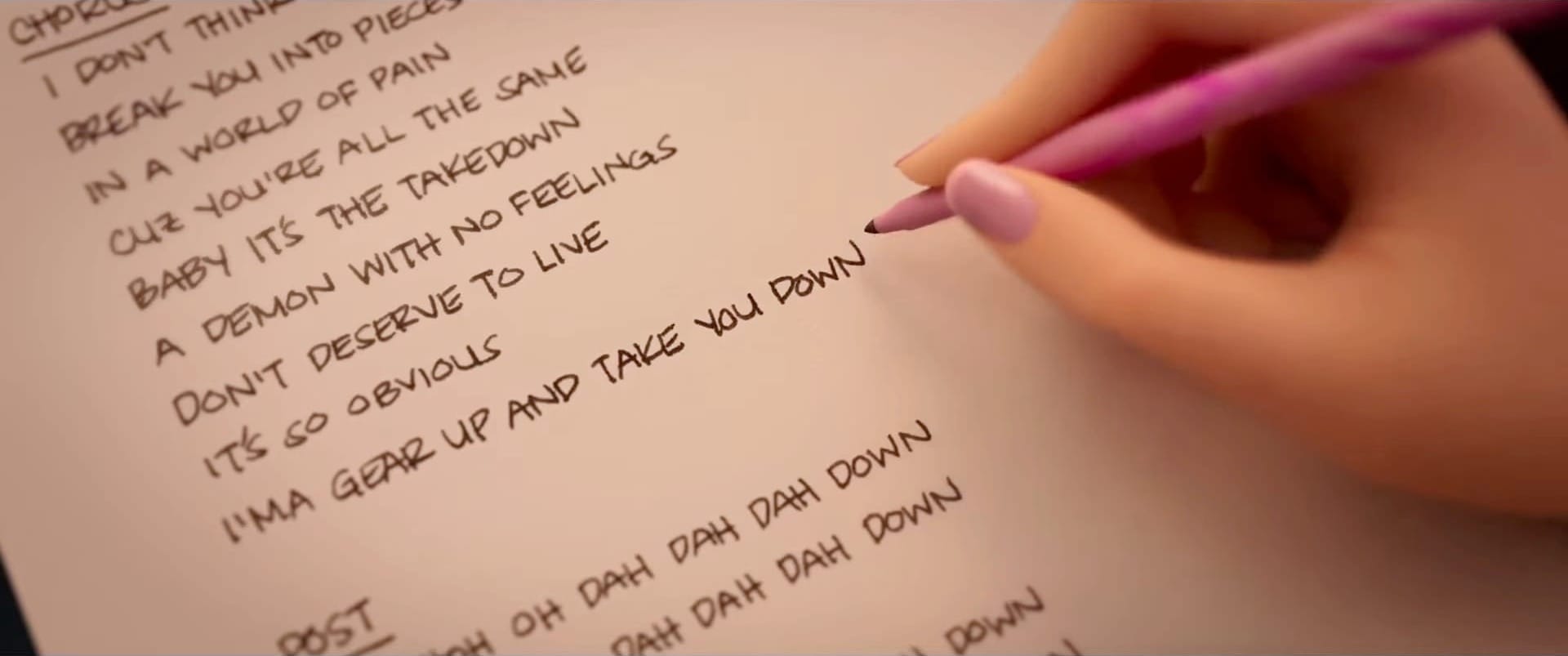

Huntr/x gears up for a Takedown

Rumi, Mira, and Zoey are used to fighting demons with magical weapons and perfectly coordinated combat. But in KPop Demon Hunters, the trio face off against a group of demons disguised as a pop band.

In their rush to confront the threat, they start brainstorming a diss track. They look for all the ways they can lyrically take apart the evil demons and win back the fans that the Saja Boys are siphoning off.

It's very personal, but Mira and Zoey don't realize how deep it goes for Rumi. The lyrics not only call out their antagonists, but also echo Rumi's internal monologue about being half-demon. She's been taught since she was a child to hide this part of herself. Her hope is that when the demon hunters secure the Honmoon and seal off Earth from the demon realm, she'll finally lose the markings and nobody will have to know.

The double target of the track is spread throughout the lyrics:

So sweet, so easy on the eyes,

but hideous on the inside

Whole life spreading lies, but you

can't hide, baby, nice try

When your patterns start to show

It makes the hatred wanna grow

outta my veins

Break you into pieces in a world

of pain 'cause you're all the same

Yeah it's a takedown

A demon with no feelings don't

deserve to live, it's so obvious

It's this unyielding anger against the Saja Boys and demons in general that Rumi fears. She's been taught to fight demons indiscriminately, but also allow herself to exist in a gray area between hunter and demon.

This all sets up for the big reveal late in the film, where demons impersonating Zoey and Mira perform Takedown at Rumi in front of a crowd and reveal her secret.

The words forming the lyrical barbs wouldn't be nearly as effective if they only showed one side of the equation. Rumi's greatest fears are losing her friends when they find out about her demonic patterns, and the fear that she's fooling herself into thinking she's not evil like any other demon. Both are serviced by the song, picking apart her psyche and breaking her down.

Making sure the insult isn't Lost in Translation

You always hurt the one you love

The one you shouldn't hurt at all

You always take the sweetest rose

And crush it till the petals fall

–The Mills Brothers, "You Always Hurt the One You Love"

Why do we hurt the ones we love? Maybe it's because we know where the metaphorical bodies are buried. Or it could be because if you pay attention to someone for a long time, you catch on to patterns. Sometimes, toxic codependence masquerades as love.

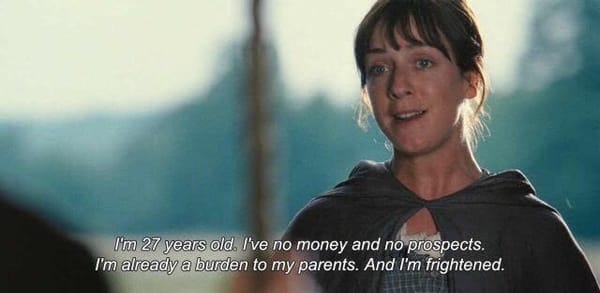

Greater intimacy provides greater ammunition for insults. Consider the Shabu Shabu scene from Lost in Translation where Charlotte does and doesn't want to talk about catching Bob having a one-night-stand with the hotel lounge singer:

CHARLOTTE

Well, she is closer to your age. You could talk about things you have in common, like growing up in the '50s. Maybe she liked the movies you were making in the '70s, when you still were making movies

BOB

Wasn't there anyone else there to lavish you with attention?

What else is there to say? It's all packed into two lines.

Charlotte knows from their first conversation that Bob is sensitive about his acting career's downward trajectory, and poking at his sensitivity toward his age. But it's also leaving something unsaid: "she is closer to your age." Closer than who? There's a possessive jealousy in Charlotte's opening but also some ambiguity. Is she annoyed that someone else got pulled into their "pod," maybe poking the bubble around what made their extended hangout special? Is she implying that she feels rejected?

And Bob refuses to engage. This is a man who is at least a little hungover, reckoning with the fact that he cheated on his wife while on the other side of the planet, and that any disappointment Charlotte feels in him can't hold a candle to what his wife could/will feel (or how his own self-hatred).

So we get deflection, but drawing from his read on Charlotte: You came to Japan with your husband, but he's never there. So you're looking for somebody, anybody to reassure you that you matter. That you're seen.

The sparse dialogue and muted look of the scene is a sharp contrast to all the high energy, colorful fun the two have had up to this point. Their lengthy, emotionally exposed conversations gave each of them all they needed to shut each other down in 30 seconds or less. Because of the heightened sense of their connection before, this low point feels especially low.

Even more insult examples

Great examples from a trio of iconic teen-focused comedies:

- "You're a virgin who can't drive." –Clueless

- "You're a blue bird. You're a brownie. You're a Girl Scout cookie." –Heathers

- "They say you're a home-schooled jungle freak who is a less hot version of me." –Mean Girls

Touré takes a line-by-line literary reading of Kendrick Lamar's "Not Like Us" (and you know how much we love a deep dive here). One important point that gets called out: Consider the difference in the intended audience for Drake's and Lamar's respective tracks. Drake speaks to the audience about Lamar (aka "Seriously. Would you look at this guy?"), but Lamar directly addresses Drake (aka "Seriously. Would you look at yourself?").

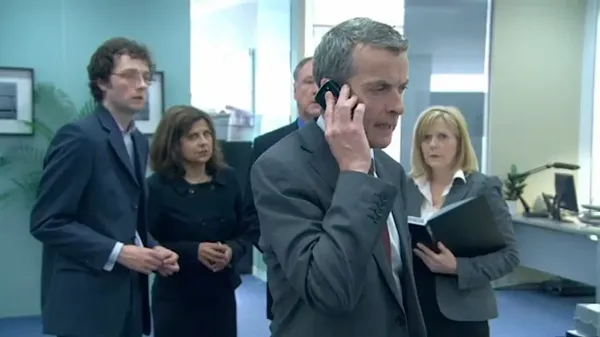

Playing into the specificity of a good takedown, and also using the self-immolation strategy of stealing your opponent's thunder by taking yourself down, take a detour to the 313 for a clip of Captain America losing a rap battle in 8 Mile.

👋 Are you new here?

Inneresting is a weekly newsletter about writing and things that are interesting to writers. Subscribe now to get more Inneresting things sent to your inbox.

And if you can't wait until next week for more Inneresting, check out the Quote-Unquote Apps Blog where we keep previous issues and other posts about screenwriting and things interesting to screenwriters.

In case you missed it...

In the most clicked link from our last issue, Katrina Gould looks at It's a Wonderful Life through a Buddhist lens, considering the importance of reframing unfulfilled dreams to keep them from causing unnecessary suffering.

And that’s what’s inneresting this week!

Inneresting is edited by Chris Csont, with contributions from readers like you and the entire Quote-Unquote team.

Are you enjoying this newsletter?

📧 Forward it to a friend and suggest they check it out.

🔗 Share a link to this post on social media.

🗣 Have ideas for future topics (or just want to say hello)? Reach out to Chris via email at inneresting@johnaugust.com, Bluesky @ccsont.bsky.social, or Mastodon @ccsont@mastodon.art