🤖 #277 - Do we want to be more human?

While it's a long way from large language models to generalized artificial intelligence in the real world, there are plenty of stories where artificially sentient beings question their humanity (and if they really need any). Frequently stories about artificial life, whether created by science or magic, focus on defining what it means to be human. What if we accepted that an artificial life could be complete without having to conform?

A.I. Artificial Intelligence wears its protagonist's desire to be a real boy on its sleeve. James Clarke looks at the direct influence the story of Pinocchio had on Kubrick’s development of A.I. Artificial Intelligence, but also the way the wooden puppet’s journey to become “real” is understood as not only a story about transformation, but maturation. Humanity as the prize for finding the righteous path. Maya Ruder dives into A.I. Artificial Intelligence, and how the film’s post-human ending maintains a hierarchy of wonder toward what it means to be human, and a sense of artificial life being somehow deficient or lacking.

Few fictional androids have gotten as much screen time to consider their humanity than Star Trek's Lieutenant Commander Data. Steve Shives outlines Data’s desire to become a “real boy,” then posits a thought experiment about what it would take for Data to have an actual experience of human life, which would require being treated by others as a human and believing himself to be a human (and all the ethical difficulties this would present). The Art of Storytelling looks back to the original description of the character, that Data would pursue becoming human, without ever fully achieving that goal. Data was conceived of as being similar to Spock: a character that looks at humanity from a somewhat removed position.

Pulling from some of the key moments where Data and those around him try to define his humanity:

- While speaking to Q, Data stresses emotional intelligence as the barrier to full humanity. Defining this particular quality, with all its neuortypical baggage, as a way of Othering himself, shows an acceptance the Othering he experiences from humans. It's an argument that negates his personhood because he does not completely conform to what is defined as normal.

- When Data attempts to construct a daughter, he tells her that the strive to become more human has its own rewards, even if it feels impossible. His daughter treats themselves as “incomplete” because of the ability to act as if human, but not to feel as if human (put another way, successful masking does not produce the expected internal response).

- Captain Picard’s defense of Data and how it is not a question of whether Data counts as human, but if he counts as sentient life. This distinction is crucial, because it grants him rights. He is seen as complete enough though not exactly human, because he can be proven to have qualities that sentient life exhibits. Not the same, but equal under the law.

In counterpoint to Data’s focus on emotional intelligence as a barrier to humanity, Greg Anderson singles out Marvin from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy as an example of why programming robots with emotions would likely lead to either the robots suffering or being insufferable. The use cases for building a robot and the social purposes of feeling, understanding, and expressing emotions don’t have a lot of overlap.

In an interview, Murderbot Diaries author Martha Wells shares the experience of writing for a non-human sentient character, and realizing her own neurodivergence in the way that Murderbot processes and interprets human actions and emotions. Justin Gregg considers whether Murderbot has the capacity for agency and experience. Would it change how people treat this android if they knew it could feel pain? What about if they knew it definitely didn’t? Magnus Söderlund pursues the argument that non-human androids like Murderbot are shown to be human-like as a way of connecting to the intended human audience. Amber from Road to Tar Valon dissects episode 6 of Murderbot to explore the tension between Murderbot’s requirement to interact with humans while simultaneously not wanting to be treated (or expected to behave) like a human. This episode brings that tension to a head when Murderbot kills a woman threatening his clients.

Taking a broader view, M. Dorobantu wrestles with whether artificial intelligence could become religious, and how humans might respond to newly devout droids. Pete Peppers focuses on Foundation’s Demerzel, the last intelligent robot in the Galactic Empire, and an adherent to the Luminist faith. The religious aspect of her character plays directly into a central conflict between her and one of the clones of Emperor Cleon when he attempts to take the same religious pilgrimage Demerzel took 11,000 years ago.

Both characters wrestle with the question of if they have a human soul, or if either of them is even an individual intelligent being. Demerzel makes a point in expressing how even though she has her faith, she still understands her obligations and duties as a robot, and how the tension between the programmed and the divine causes her pain (but cannot change her actions).

And what of questions beyond individual sentience? Dr. Danielle Sanchez considers how Star Wars has mostly allowed the question of droid sentience to take a back burner in focusing on them as tools instead of as an oppressed people. The lack of a droid revolt or larger efforts for droids to assert their own sentience allows for a galaxy where Empire and Republic are equally tolerant of an enslaved automated underclass. Allen Xie digs deep to look for examples of robot revolts in Star Wars, and the ways that the society of this series develops its legal understandings of droid sentience and responsibility as a means to prevent future droid uprisings.

👋 Are you new here?

Inneresting is a weekly newsletter about writing and things that are interesting to writers. Subscribe now to get more Inneresting things sent to your inbox.

And if you can't wait until next week for more Inneresting, check out the Quote-Unquote Apps Blog where we keep previous issues and other posts about screenwriting and things interesting to screenwriters.

In case you missed it...

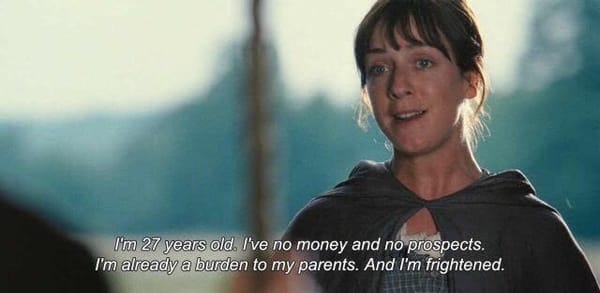

In the most clicked link from our last issue, Nerdwriter asks why people always end up running in romantic comedies.

What else is inneresting?

- Ron Currie and Martin Skladany propose a writer-owned studio, taking cues from the original United Artists and Blumhouse, to suggest what this business model could look like.

- Nathan Lockard shares how his kid is waging Sun-Tsu-worthy psychological warfare to convince Dad it’s time to buy a Switch 2.

- If you like robots, horses, and indie-folk-rock song cycles about robot horses wrestling with existential questions, give a listen to Rock Plaza Central's Are We Not Horses?

And that’s what’s inneresting this week!

Inneresting is edited by Chris Csont, with contributions from readers like you and the entire Quote-Unquote team.

Are you enjoying this newsletter?

📧 Forward it to a friend and suggest they check it out.

🔗 Share a link to this post on social media.

🗣 Have ideas for future topics (or just want to say hello)? Reach out to Chris via email at inneresting@johnaugust.com, Bluesky @ccsont.bsky.social, or Mastodon @ccsont@mastodon.art