A villain's presence without being present

There's a twist in this Villaintine's Month post: The villain's not who you think it is. And they might not even exist?

Just because a protagonist and their adversary don't directly trade blows or bon mots doesn't mean the villain feels absent from a story.

Looking at some examples, we'll pick out some ideas on how to show the audience how a parasocial relationship between hero and villain can create fear and dramatic tension.

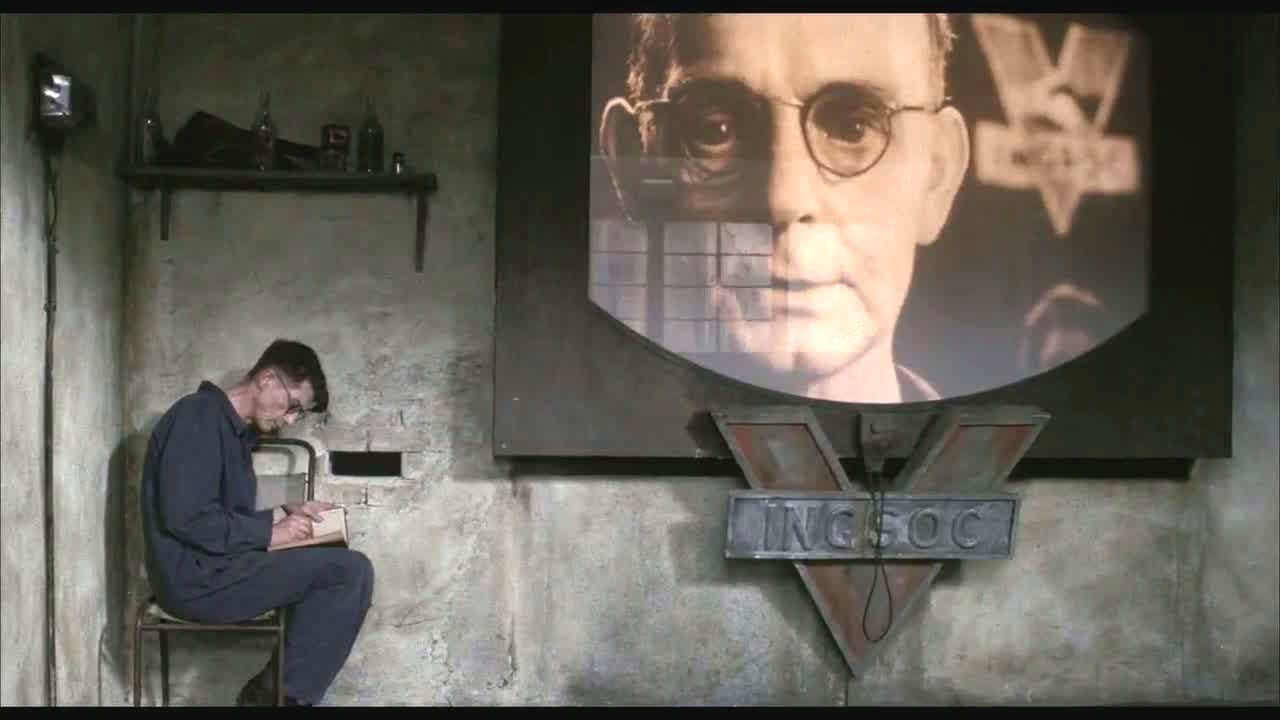

Big Brother (1984)

Big Brother is watching you. That's the threat underlying the totalitarian state of Oceania. Anything you do may be seen or reported to the state, and even the most devoted party member may fail to appear properly loyal at all times.

Winston Smith's job is to retcon past news and public information to make sure it conforms to the present statements of Big Brother. Even though he knows his job is about building lies, he still goes through with it. That sense of fear translates to the audience, and the story continues to tug on that thread of cognitive dissonance.

It's not just the telescreens and the posters and the fanfare. Because of how citizens are expected to inform on each other, every person could be an extension of Big Brother. This allows the party's leader to be nowhere and everywhere at every moment.

Ask yourself...

- If you're writing a villain who stays in the shadows, who or what can represent their influence on the outside world?

- If the antagonistic force is a system or group without a de facto leader, is there a figurehead? Does someone represent the larger whole, even if it's only to your protagonist?

The Mysterious Force (Phineas & Ferb)

Candace has one defining goal: Bust her brothers and convince her mom that those two boys spend every Summer day building dangerous experiments in the back yard. But every time she tries, something happens to remove all the evidence right before her mother looks where Candace is frantically pointing.

This is part of what keeps Candace from seemingly like a villain on the show. Yes, she wants to thwart the show's protagonists, but she always fails. And those failures aren't a direct result of Phineas, Ferb, or their friends working against her.

Candace gives a name to the unlikely chain of cause and effect that hides the boys' handiwork: The Mysterious Force. She believes so strongly in this unseen arch nemesis that she speaks to it directly. She even calls upon it in the hopes that when it removes Phineas and Ferb's devices it will take a robot invasion from another dimension with them.

And just like she expects, the robots and inventions are swept away before she can finally get her mom's attention, allowing Candace to feel like she's the one who saved the Tri-State Area.

Ask yourself...

- Do you have a character who feels picked on or singled out for misfortune? Where could they see a source for their bad luck? What evidence do they collect?

- Does the audience need to believe in it, or should they be allowed to see more than the character? Is it important to fool the audience, or should they be in on the joke?

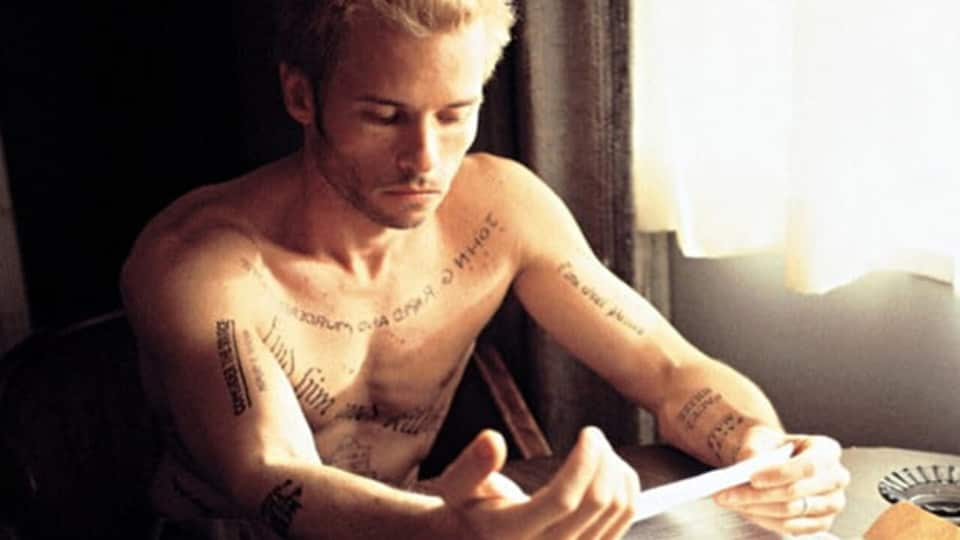

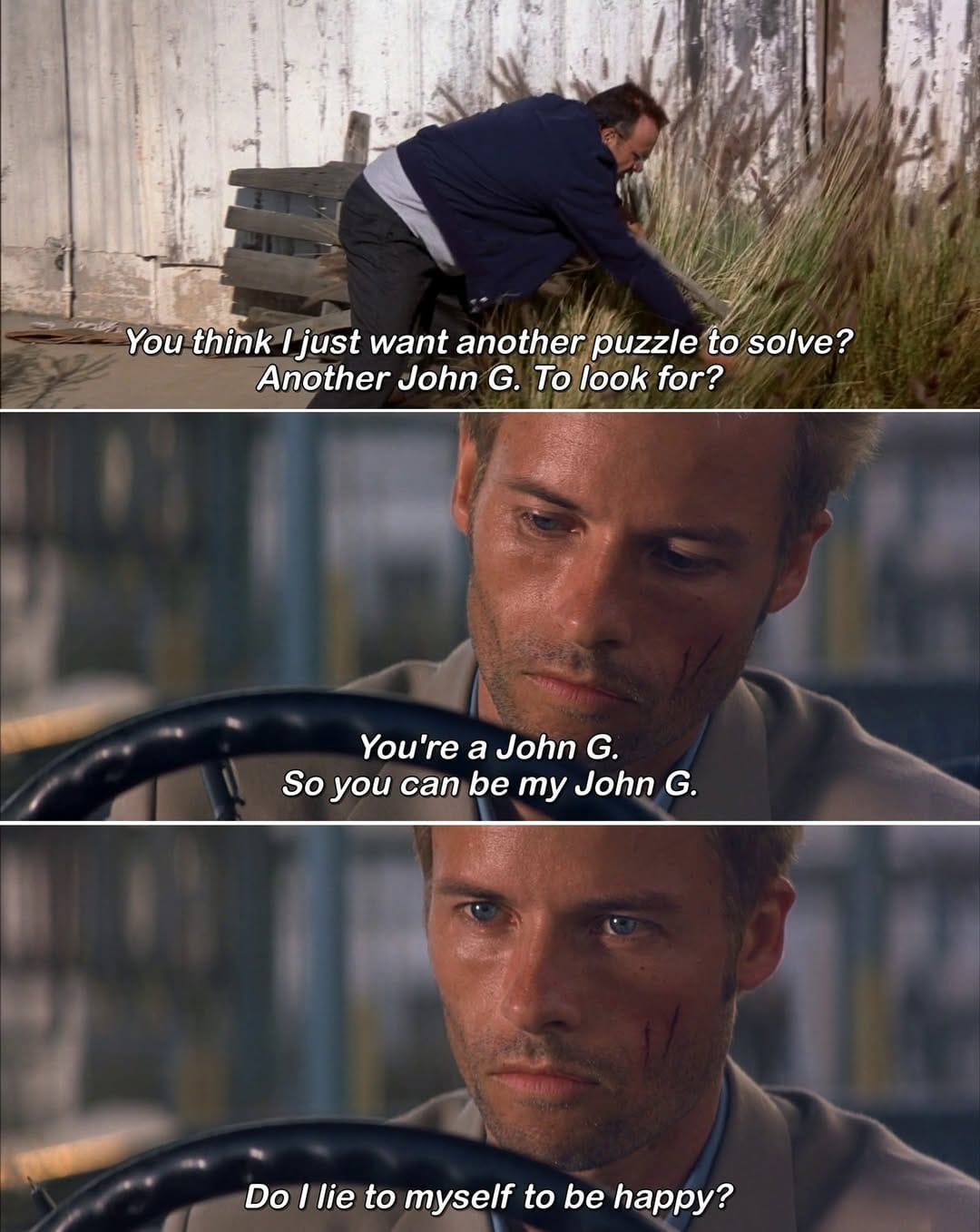

John G. (Memento)

Leonard has this condition.

We're introduced to Leonard and the systems he uses to compensate for his specific form of amnesia that prevents him from forming new memories, but keeps his old memories intact. Polaroids. Handwritten notes. Tattoos for crucial facts that he doesn't want to lose in pursuit of his wife's killer.

And every one of these tools is flawed, leaving Leonard open to manipulation.

Leonard has a burning need to seek out John G. and kill him, even though this name only came to him after he developed his memory disorder. It piggybacks on his existing knowledge that he had a wife, she's dead, and he hit his head.

The story spends time developing Leonard's belief not only in his system, but that the end will come when he finally catches John G. He's Leonard's white whale. He's the focus of all his actions.

And he also is a lie. Teddy, who says he's been helping Leonard track John G., admits that he's convinced Leonard to kill multiple men (apparently drug dealers) that he convinced Leonard were the man he was looking for. Because Leonard can't remember those murders, Teddy can continue using Leonard as a perfect, oblivious hitman.

Ask yourself...

- Who benefits from inventing a villain? How would they create believable evidence given what they know and their resources?

- Why go through the trouble of crafting an imaginary villain? What benefit can a character gain through the deception?

Ozymandias (Watchmen)

Depending on which version of the character you're experiencing, former vigilante Ozymandias either blasts multiple cities across the globe with beams of energy that frame Dr. Manhattan as a villain, or he drops mutated squid in major city centers to fake an alien invasion.

And he does this in pursuit of world peace.

Don't let that fool you. Ozymandias may succeed in temporarily getting the leaders of countries around the world to stop fighting amongst themselves and begin preparing to defend against planetary threats, but it costs millions of innocent lives. He just believes that he's killing fewer innocent people than global nuclear war would.

Throughout the narrative, Ozymandias protects his secret through various means, including staging a very public attempt on his life. The other characters have spent time laying the groundwork for this twist with reaffirming how smart, wealthy, and influential Ozymandias is. Not only do the other characters the audience follows in the story piece together what his plan is, creating this believable fictional villain for the rest of the world to fear, but he relishes in his victory to their faces. The heroes realize they had the solution to the mystery, but they were just a little too late in reaching their conclusion.

In one version, he manipulates the world's fear of a superhuman with no clear check on his powers. In another, Ozymandias takes humanity's fear of the unknown and overloads it with an event so strange and with such a high body count, that an unlikely possibility becomes the accepted truth.

Ask yourself...

- What fears do people in the world of your story already have? What genuine fears can be manipulated by directing those fears at a manufactured threat?

- Big schemes require massive egos and resources. When a character creates a fictional villain, how can you suggest to the audience that their desire is strong enough to see it through? What skills and resources must they have to pull it off?

No matter the genre, a villain hiding behind the scenes can make the hero seem smaller and the odds of victory even more slim.

But in all these examples, it's not just about how far the villain's influence reaches, but about how much space they take up in the protagonist's head (rent free). Even if they never meet, or one of them doesn't exist, there's a connection that demands confrontation and resolution.