🏳️ Inneresting #255 - Taking the L

When there's no way to win, what's there to do?

There's always a possibility for a protagonist to fail. The tension in a story is tied to whether a hero (or heroes) will win or lose.

But sometimes, a story follows someone convinced there's no chance of victory. So how does a protagonist keep going even when they know that nothing they do will give them the happy ending?

Kate O’Brien compares Rocky to the tradition of scrappy underdogs that audiences love to root for. For characters like Rocky and Adrian, their story isn’t about fame, glory, and fabulous prizes. It’s about respect, both self-respect, and earning the genuine respect of others. Balboa takes on the burden of a fight he knows he’ll lose because he believes that going the distance will make him a man deserving of respect and love.

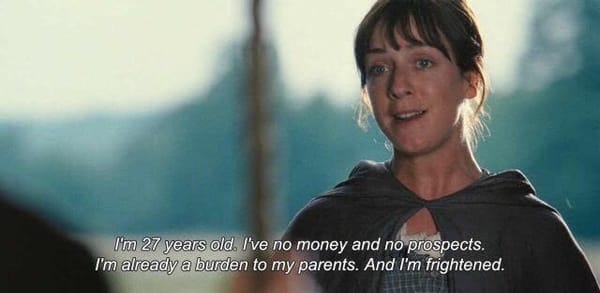

In this clip, he lays it all out for Adrian. He sees no way that some random palooka like him is going to take a title away from a seasoned champ. Victory feels hopeless, but he finds another way to see the problem. He renegotiates the stakes:

Can we just bask in the visual poetry of the arena scene? Rocky, diminished under the looming image of Apollo Creed, letting the reality of his chances sink in. Shot after shot, Rocky gets smaller and smaller. It's just 👨🍳😘👌

Grayson Quay looks at Rocky as drawing multiple parallels between the prize fighter and Jesus Christ, suggesting how to view Balboa as “victorious in defeat:”

But before we ever see Rocky, we see another face, the face of Christ painted on a mural above the ring. The first shot is a close-up. His hard-set countenance, haloed in light, suggests a stern Pantocrator, but as the camera zooms out we see that instead of the book and blessing of the Last Judgment, His hands hold a Host and chalice. Thank God for this shot. It is only with a wounded-yet-glorified Christ looking on, offering His broken body and spilt blood in solidarity with a suffering world, that Rocky can face the ultimate opponent and “walking in the way of the Cross … find it none other than the way of life."

Aïche Martine Thiam points to the daring suicide mission of Rogue One as part of the reason why she considers it the best Star Wars film since the original trilogy. It’s a scenario where the individuals lose their lives, but their efforts win the battle:

Jyn and co., then, have not died for nothing, but this doesn’t make their story any less tragic. Theirs is a sober and thankless tale of small people doing big, important things that help shift the balance of power, but who probably won’t be remembered beyond that.

There's a total awareness in the characters that this is where their story ends. Jyn’s speech to the volunteers onboard Rogue One doesn’t sugar coat it. There’s no guarantee of success for their mission, and no guarantee that they’ll survive. But she’s determined to take every chance she can to punch a hole in the seemingly impenetrable armor of the Empire. It's choosing defiance in the face of inevitable defeat.

In an extreme case, everyone on the planet knows it's game over. These aren't stories where someone's prepping to blow up the asteroid speeding toward Earth, or we're following the President's prepping for how to save as many pieces as possible. These are just people, their lives upended by a countdown to death.

Stef from Quality Culture considers how Seeking a Friend for the End of the World shows an array of potential reactions to learning that the end of the world is definitely about to happen. This is made even more intense as this film chooses to actually go through with the end of the world instead of allowing for a last second save.

Matthew Huston points to Lars von Trier’s Melancholia as an example of a personal apocalypse movie, focused on two sisters and how awareness of the impending destruction of the planet leads them to trade roles: The caretaker sister suddenly feels unequipped to be of service, and the other moves from depression to peaceful acceptance.

The Functional Melancholic meditates on why people romanticize the end of the world, and how people could see the impending destruction of all life on the planet as a break from the noise of everyday life. People won’t necessarily react with panic and fear, because they have an unavoidable reason to focus on what matters instead of what’s keeping them alive:

”In The Walking Dead, nobody worries about car insurance.”

👋 Are you new here?

Inneresting is a weekly newsletter about writing and things that are interesting to writers. Subscribe now to get more Inneresting things sent to your inbox.

Previously on Inneresting…

In case you missed it, last issue’s most clicked link, Joe Wilkins collects examples of companies walking back their commitment to replacing humans with AI Agents as they realize that AI isn’t fully baked yet.

What else is inneresting?

- Harmony Colangelo looks back at 28 Days Later and sees parallels between the hostility Jim faces in the film, and the hostility transgender people experience in real life.

- Corridor Digital use a 360 degree camera and a clear ball to capture a bowling ball’s eye view of hitting the pins.

- Annie Mueller with a reminder that when considering human rights, there is no neutral middle ground. You either support equal rights for all, or you wind up giving support to those who argue that different classes of people only deserve some rights.

And that’s what’s inneresting this week!

Inneresting is edited by Chris Csont, with contributions from readers like you and the entire Quote-Unquote team.

Are you enjoying this newsletter?

📧 Forward it to a friend and suggest they check it out.

🔗 Share a link to this post on social media.

🗣 Have ideas for future topics (or just want to say hello)? Reach out to Chris via email at inneresting@johnaugust.com, Bluesky @ccsont.bsky.social, or Mastodon @ccsont@mastodon.art.