🗑️ Inneresting #259 - It's all just trash

We're talking about the Garbage Can Model and how a description of chaotic organizations can help writers think about their minds and their craft.

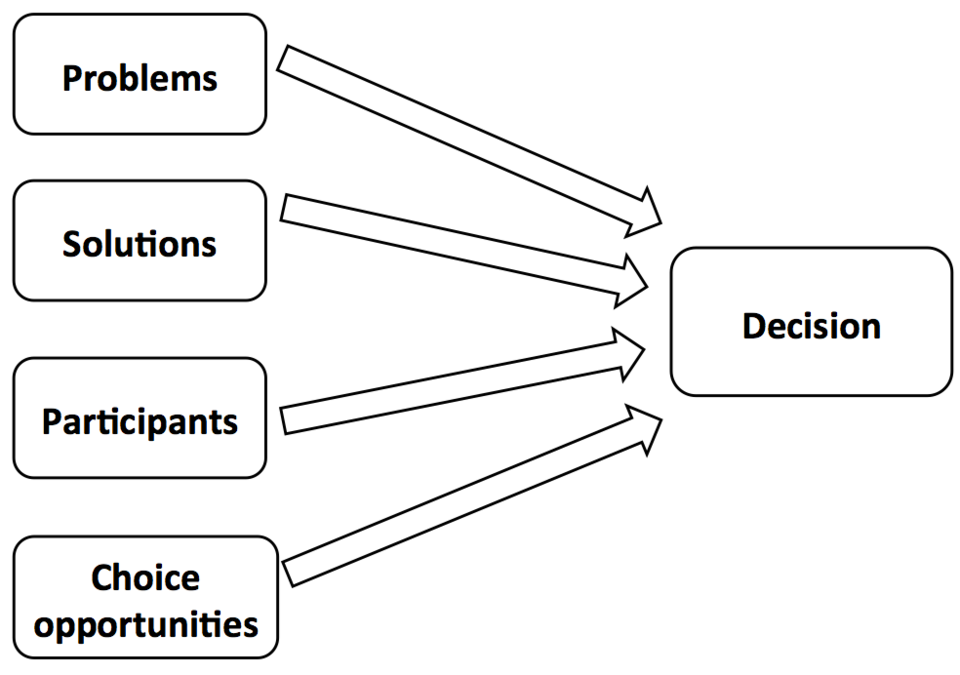

In 1972, the paper A Garbage Can Model of Organizational Choice was published by Michael D. Cohen, James G. March, and Johan P. Olsen. The basic premise relates to how decisions get made within organizations that don't seem to have any obvious structure or hierarchy.

Imagine a big pile of problems, possible solutions, and available people. And when there's an opportunity to take action and make decisions, it all gets thrown into a big trash bin to see what fits together.

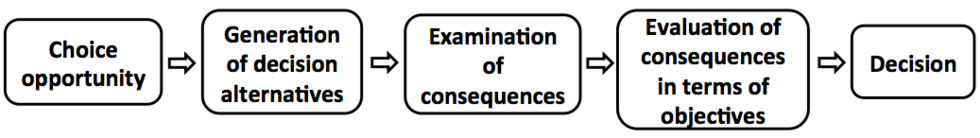

The decision making process in a structured organization looks something like this:

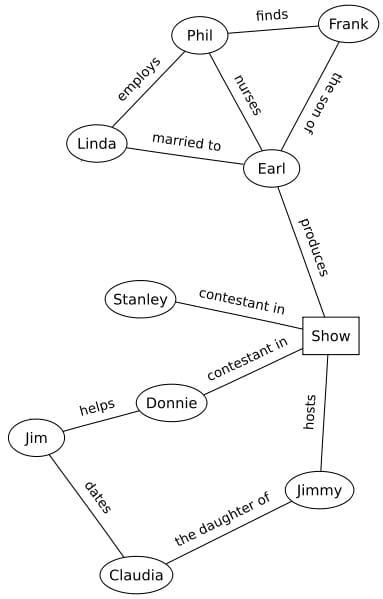

But in the chaotic Garbage Can scenario, everything gets thrown together before there's an opportunity to make a decision. It looks more like:

While the work on this concept is about anarchic organizations, we can apply it to individual idea management. In episode 417 of Scriptnotes, guest Aline Brosh McKenna talked about her process of holding on to ideas loosely:

...when I go to sleep I try and think about something that I’m noodling on or have to solve. And I don’t think I wake up instantly with the answer but I do try and noodle on it because I know that that’s a fertile period. I will say like Rachel [Bloom] and I frequently had this conversation – I don’t write things down very often because I feel like if it’s a good idea it will persist and it will return to me. And I know a lot of people who think I’m insane who are real note-takers. And for them they need to see it concretized. If I start writing on an idea too soon I’ll kill it. It’s like I’ve over-watered the plant.

So I have to kind of keep it in a back-burnery place where only my subconscious is working on it until it’s kind of formed before I start putting voice to it...

Giving snippets of ideas time to bump into each other can let a writer iterate on the initial idea or find some creative mash ups, like when a solution in the bin matches up with a problem. For example:

Jaws on a spaceship → Alien

Chinatown for kids → Who Framed Roger Rabbit?

A cute dog + Basketball + There's nothing in the rulebook that says a dog can't play basketball → Air Bud

Also consider this model when thinking about conflict and relationships in a story. In real life, there aren't set protagonists and supporting characters. Everyone has their own problems, solutions, and abilities, and these things may or may not line up to resolve a story. Rebecca Gillman writes about this kind of storytelling in her essay on You Can Count On Me.

The story sets in motion when Terry shows up from out of town to ask his sister Sammy for a loan so he can pay for his girlfriend's abortion. But this isn't the problem to carry the weight of the whole film. The siblings were orphaned at a young age, depend on each other, and each bring their own problems and solutions to this moment where they're both together and can take action.

For example, Terry takes his nephew Rudy to meet his father, undercutting Sammy's choice to keep Rudy, Sr. out of her son's life. Terry identifies a problem and a solution he thinks he can handle:

Terry and Rudy, Sr. fight, Terry gets arrested, and Rudy, Jr. watches from the back of a police car as Rudy, Sr. tells a cop that he has no idea who the kid is.

This does not resolve the problem as Terry expected. But it makes sense he would try it that way. He and his sister don't have clear communication and boundaries. Their relationship is messy and entangled in a way that's difficult to live through, but great for creating conflict and tension on screen.

Taking this idea further, consider ensemble cast stories. Magnolia, Go, annual discourse generator love, acutally, or The Rules of the Game. Disparate characters brought together at a moment where they all have an opportunity to make a big change. Each character brings to the story their problems, ideas solutions, and the time and energy they have available.

It all gets dumped into the garbage can, and the pieces start connecting for the writer in a way that (hopefully) helps the audience seem them connect, as well.

👋 Are you new here?

Inneresting is a weekly newsletter about writing and things that are interesting to writers. Subscribe now to get more Inneresting things sent to your inbox.

And if you can't wait until next week for more Inneresting, check out the Quote-Unquote Apps Blog where we keep previous issues and other posts about screenwriting and things interesting to screenwriters.

Previously on Inneresting…

In case you missed it, last issue’s most clicked link, Aaron Sorkin, discussing The Trial of the Chicago 7, describes adapting real life as making a distinction between journalistic accuracy and the truth of the moment.

What else is inneresting?

- Paolo Cherchi Usai on three ways something can be classified as unfilmable: Physically, Ontologically, and Morally.

- Laura Goodman shares the Kafka-esque story of getting her children's allergies properly diagnosed.

- Inneresting is five years old → The traditional fifth anniversary gift is wood → Here’s Nick Offerman giving a tour of his woodshop and suggesting how to get started with woodworking.

And that’s what’s inneresting this week!

Inneresting is edited by Chris Csont, with contributions from readers like you and the entire Quote-Unquote team.

Are you enjoying this newsletter?

📧 Forward it to a friend and suggest they check it out.

🔗 Share a link to this post on social media.

🗣 Have ideas for future topics (or just want to say hello)? Reach out to Chris via email at inneresting@johnaugust.com, Bluesky @ccsont.bsky.social, or Mastodon @ccsont@mastodon.art.