🗣️ Inneresting #260 - How long do we need to talk about this?

Sometimes we use science to talk about craft, like when a study about conversations can teach something about dialogue.

Adam Mastroianni shares a breakdown of a study he did on the perception of conversation length. There's some correlation between writing dialogue and better understanding how real people think about the conversations they're having. Did they believe their conversation was too short, too long, or just right?

In this issue, the blockquotes featured will be from Mastroianni's post, highlighting the jumping off points to talk about writing better dialogue.

[A] conversation is like a ride down the highway: you’re really only supposed to exit at certain times. But the exits themselves are pretty spread out, so you’re probably not going to be on top of one at the exact moment you start feeling ready to leave. Technically, you can get off the highway between exits, but you might have to drive through some bushes or crash through a wall—that’s what it feels like to, say, leave in the middle of someone’s story. So instead, you wait until the next exit comes (and you end up as a “too long”), or you get off before you really want to (and you end up as a “too short”). This strong set of conversational norms keeps things both orderly and somewhat dissatisfying.

We see one of these moments where the conversation misses an exit and swerves into traffic in Jaws:

That moment, right when Hooper and Quint drink to each other's legs is a natural off-ramp for this conversation, but Brody speaks up and shifts gears. Hooper's still continuing the previous conversation with his jokes until Quint's hand on his arm signals "We're moving on."

What started as a playfully competitive bonding session ends with a dire warning about the beast they're hunting, and a better understanding of the trauma that drives Quint's bloodthirst. But just because the subject becomes disturbing or uncomfortable, it's not going to necessarily bring the conversation to a complete halt:

In another [conversation from the study], two girls are talking about taking a year off of school, and one asks, “Oh, but don’t you have to re-do your financial aid paperwork?” and the other goes, “...I don’t get financial aid.” A silence pervades, then one of the girls starts playing with her coffee cup and goes, “This cup is so loud!”

The Power of Conversation in The Hangout Film

James Dewayne defines a hangout movie, stressing the idea that because the focus is more on getting to know the characters rather than following their pursuit of a dramatic goal, dialogue is what holds the audience’s attention. How the characters speak and what they spend time talking about lets the audience into their world:

That question of how long a conversation will or should last gets tied up in how long this hangout is going to be. Which brings us to a very special hangout movie (series)...

Before Sunrise Talks About Love

Here’s the first crazy thing that happened: 57 of our 183 pairs talked for the entire 45 minutes. We literally had to cut them off so they could fill out our survey before we ran out of time. [....] We specifically told people to talk as long as they wanted to, but when they came out of the room, almost all of them said, "I didn't talk for as long as I wanted to."

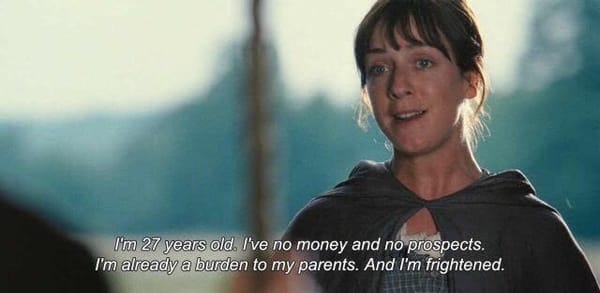

Aron from Just One More Thing takes a panoramic view of the entire Before trilogy, focusing on how this love story is told through an extended conversation:

Specifically in Before Sunrise, the tension of the story comes in how long they can keep the conversation going. These two young, clever, very thirsty people are trying to make the most of the time they can potentially spend together over the course of one night. They need to keep finding things to talk about, or they'll wind up like Wile E. Coyote and run out past the cliff's edge and see there's nothing left to stand on.

But characters can't just talk about anything and have it work. For some examples of directions to take this kind of chat, Steph Balzer covers the value of good questions, and considering how to prompt others to share more of themselves.

Opposing Conversational Goals

[T]hese conversations happened out in the wild, where they might have been ended by external circumstances. Maybe the “too long"s were, say, trapped on an airplane and unable to escape their unwanted conversation; maybe the “too short”s were having a lovely chat when their boss told them to get back to work.

When do external factors force characters to keep talking, or cut things short? Consider the episode of Parks & Recreation where Leslie and Ron's workplace proximity associates lock them in the Parks Department office overnight to bury the hatchet. There's the external pressure of the space that they're stuck in, along with the opposing character goals: Leslie wants to talk it out, Ron does not.

The quick cuts between Leslie's methods emphasize how much of each tactic we need to see to get the joke before moving on. While the length of time they're stuck together is long, these small bursts of conversation are punchy and keep the tension bubbling.

When Ron finally does give Leslie the satisfaction of an explanation, we get a longer stretch of their conversation together, and an overall slower pace to let the emotional beats land:

But even with this slower dialogue scene, the conversation ends close to the point where there's nothing left to learn about the conflict between Leslie and Ron. It's time for them to move forward, and we cut ahead with them.

Conversations have to end sometime

Mainly, conversations seem to end at a time that nobody desires.

What's going to frustrate your characters about their conversation? Are they having trouble finding the right words to say? Is some external dramatic force going to interrupt them? Are they going to find themselves stuck next to the big talker who can't take a hint because, say, there's a bomb on the bus?

To make a conversation more true to life, most of the time it shouldn't have a mutually enjoyable resolution. So pop quiz, writer: Your characters are having a conversation. It's going to end when neither of them wants it to. What do you do? What do you do?

👋 Are you new here?

Inneresting is a weekly newsletter about writing and things that are interesting to writers. Subscribe now to get more Inneresting things sent to your inbox.

And if you can't wait until next week for more Inneresting, check out the Quote-Unquote Apps Blog where we keep previous issues and other posts about screenwriting and things interesting to screenwriters.

Are you subscribed to Scriptnotes on YouTube?

We've started pulling highlights from the conversations on Scriptnotes and putting them into a condensed video package. Check out this example where Greta Gerwig shares ways to guide actors through the text, and putting more of the internal rhythms of a conversation on the page:

Remember to like, subscribe, and make fancams of Scriptnotes producer Drew.

Previously on Inneresting…

In case you missed it, last issue’s most clicked link, Rebecca Gillman writes about the messy, interconnected problems of the characters in her essay on You Can Count On Me.

What else is inneresting?

- Apologies for ruining the magic, but Alex Boucher explains the camera and puppeteering tricks that allowed the Muppets to come to life in the real world.

- Marianne Dhenin on the rising use of air conditioning in the Middle East, and how the pivot away from less eco-destructive methods of building cooler spaces started with (you guessed it) British Colonialism.

- Mario became part of the establishment long ago. Josh Broadwell declares Donkey Kong Nintendo's working-class hero.

And that’s what’s inneresting this week!

Inneresting is edited by Chris Csont, with contributions from readers like you and the entire Quote-Unquote team.

Are you enjoying this newsletter?

📧 Forward it to a friend and suggest they check it out.

🔗 Share a link to this post on social media.

🗣 Have ideas for future topics (or just want to say hello)? Reach out to Chris via email at inneresting@johnaugust.com, Bluesky @ccsont.bsky.social, or Mastodon @ccsont@mastodon.art