🧬 Inneresting #262 - Human After All

or: How I Learned to Stop Trying to Turn Off the Feelings

Marvin Gaye said, "Great artists suffer for the people." The First Noble Truth of the Buddha is The Truth of the Existence of Suffering. There are enough popular examples of the tortured artist stereotype to fill an endless number of listicles.

Artists are human. Humans suffer. Therefore, artists suffer and show it to the rest of us. Right?

Maria Popova looks at Carl Jung’s reasoning that suffering may play some role in the creative person’s life, but that true creativity is about freeing oneself from psychological delusions. Matt Webb suggests that for creative people, forcing ourselves to be something we're not is a source of suffering, and instead we should take that which we are compelled to do and treat it not as a personal flaw, but a personal signature.

Overcoming that suffering to produce The Work sometimes requires a very human need: Relationships. Mason Currey tells how James Joyce convinced Italo Svevo to return to writing after over a decade of inertia, leading to both of them finding writing success. Anu from Working Theorys brings this idea to the conversation about AI, and how relationships and trust can't truly be faked by LLMs, and that relational labor could remain essential in a more automated world.

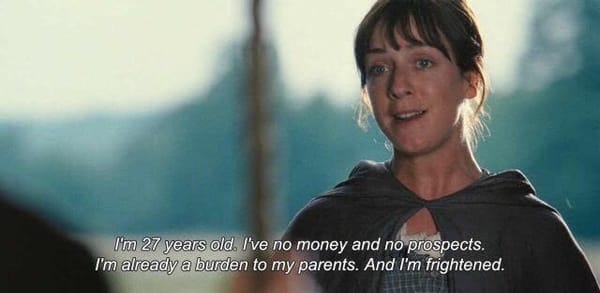

One of the ways science-fiction often questions the sentience or humanity of an artificial intelligence involves asking if it can feel; if it can suffer. Michael D. Nelson looks at the connection between his therapy clients and Lieutenant Commander Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation. Nelson calls emotions humanity's birthright, and that the character arc of Data learning to recognize, express, and manage emotions reflects on what it means to be human:

Because it's understandable to wish for an off switch for feelings. To shut out anything from the reminders that the world is on fire, to more personal, private fires consuming you and your attention. But Nelson encourages us to see our suffering and unpleasant emotions as a gift, directing us toward the parts of us that need attention and healing.

[Heidegger’s] answer is that our being is totally, utterly bound up with our finite time. So bound up, in fact, that the two are synonymous: to be, for a human, is above all to exist temporally, in the stretch between birth and death, certain that the end will come, yet unable to know when. We tend to speak about our having limited amount of time. But it might make more sense, from Heidegger's strange perspective, to say that we are a limited amount of time. That's how completely our limited time defines us.

– Oliver Burkeman, Four Thousand Weeks

If art requires humans, and humans exist as a limited amount of time, then suffering claims part of that time for itself. A human suffering is not necessarily going to be a human creating.

But if understanding suffering is important to being human, and art requires being human, it doesn't mean that there's no room for suffering. It's going to be there. But how much space must we hold for that suffering as it encroaches on our limited time?

👋 Are you new here?

Inneresting is a weekly newsletter about writing and things that are interesting to writers. Subscribe now to get more Inneresting things sent to your inbox.

And if you can't wait until next week for more Inneresting, check out the Quote-Unquote Apps Blog where we keep previous issues and other posts about screenwriting and things interesting to screenwriters.

It's been a long road, getting from there to here

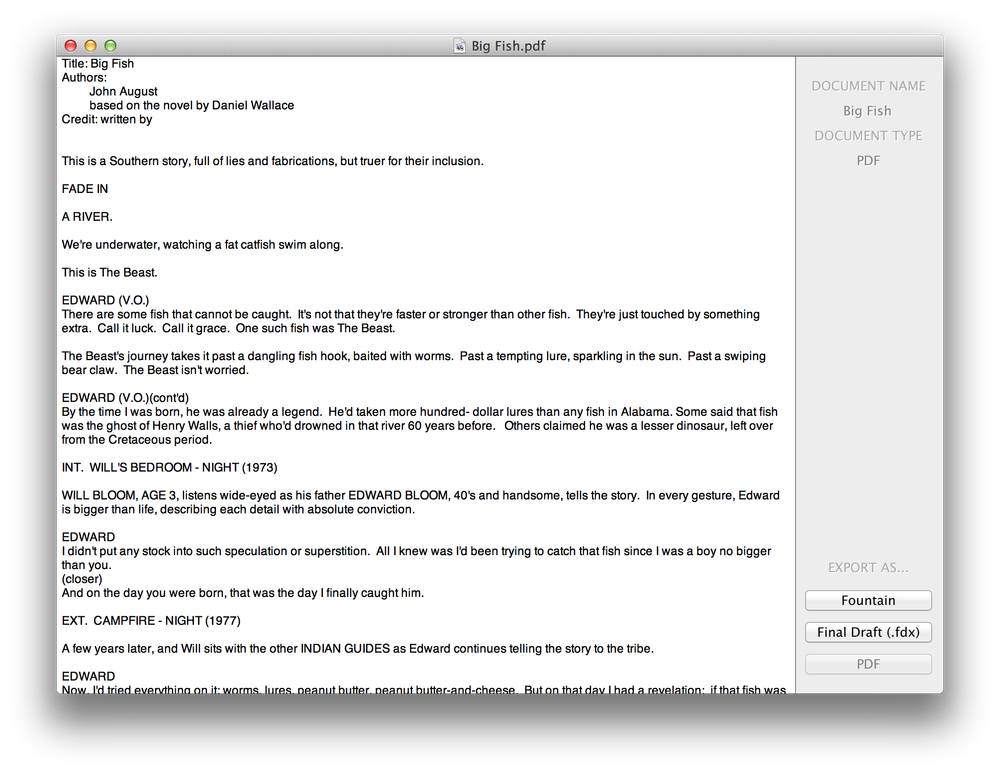

This week, John shared a visual timeline of the Highland app, from version 0.0 to its current form as Highland Pro.

Come for the screenshots of UI changes (the app version of old pictures of now embarrassing haircuts), but stay for a look at the principles that have stayed true from the beginning: the desire to create a better way to write.

Previously on Inneresting…

In case you missed it, last issue’s most clicked link, Firewood Media peels back the layers of The Teddy Perkins-focused episode of Atlanta:

What else is inneresting?

- Pour one out for AOL's dial-up service by learning from The Sacred Gamer what a dial-up modem's sounds mean.

- Mark Banchereau on the campaign to replace the Mercator Projection with a map that more accurately depicts land-masses.

- Alex Boucher on the craft of getting dogs to act, including a reminder that dogs can be good actors without understanding that they are acting.

And that’s what’s inneresting this week!

Inneresting is edited by Chris Csont, with contributions from readers like you and the entire Quote-Unquote team.

Are you enjoying this newsletter?

📧 Forward it to a friend and suggest they check it out.

🔗 Share a link to this post on social media.

🗣 Have ideas for future topics (or just want to say hello)? Reach out to Chris via email at inneresting@johnaugust.com, Bluesky @ccsont.bsky.social, or Mastodon @ccsont@mastodon.art